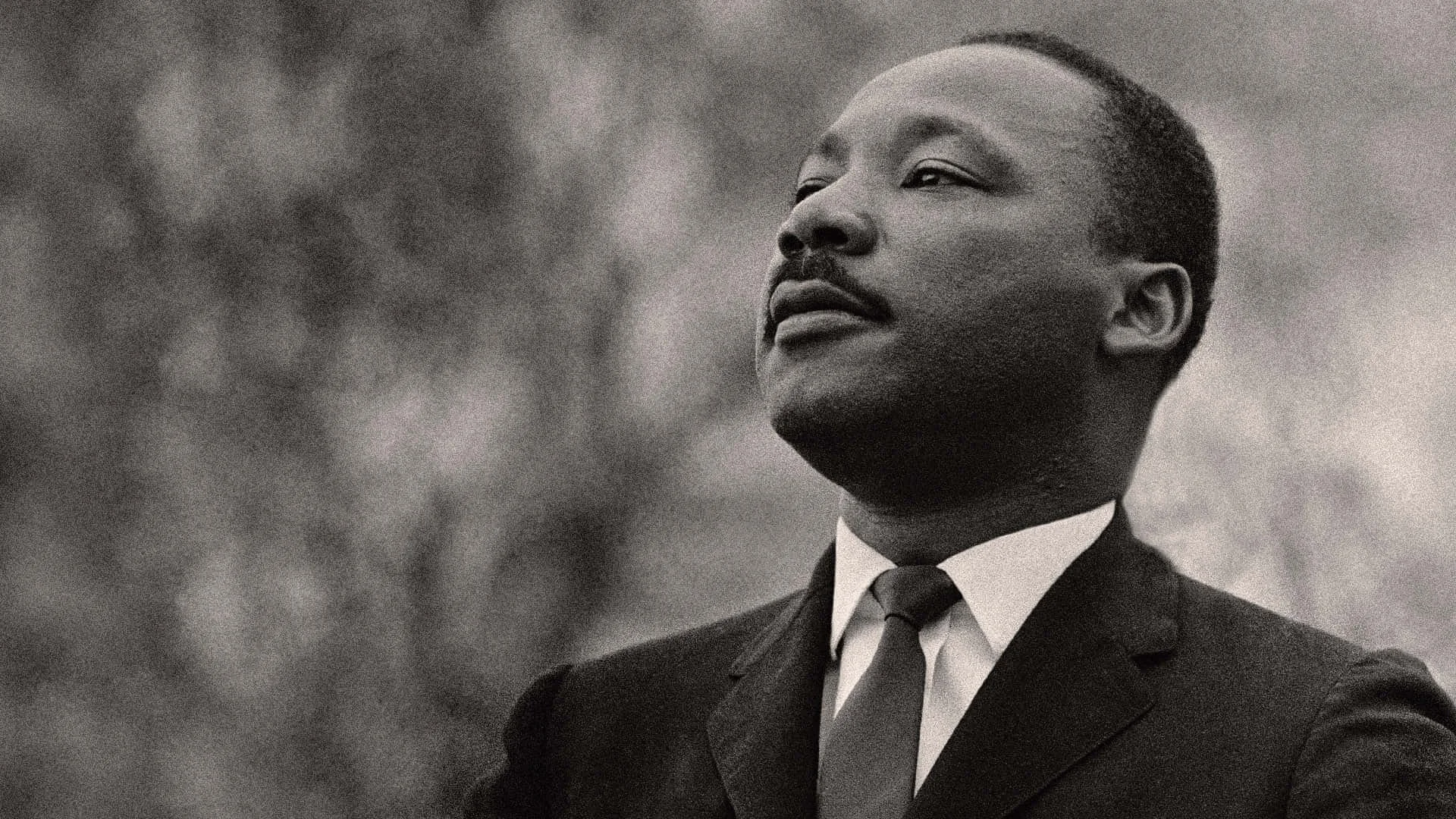

Martin Luther King Jr. on Love & Community

Today the United States commemorates the life and work of Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. We honor King as a civil rights activist who dedicated his life to serving others. As a federal holiday and National Day of Service, on this day we honor King’s legacy by serving our communities. King is most known for his nonviolent campaigns against injustice, including leading a boycott against segregated buses in Montgomery, Alabama, multiple forms of nonviolent protests against segregation and discrimination in Birmingham, Alabama, and the Poor People’s Campaign, which King did not live to see completed. What is less often discussed is that King’s nonviolent protests were not a philosophy in themselves but a practical outworking of a rich ethic of love.

Love as King used the word is not the kind of thing whimsically portrayed in Hallmark movies; it’s not about feelings or affection. Love for King is about one’s attitude and actions. For this reason King associated his ethic of love with the New Testament concept of agape and called it God’s love & “operating in the human heart.” This kind of love is not based on merit, on someone being loved because they are a good or deserving person. This kind of love is not reserved for a select group but is bestowed on everyone. This kind of love is not static, but creative. Specifically, agape is a motivating force to create community, the beloved community as King often called it.

The community that King envisioned was a place where there is justice, brotherhood, and goodwill. These three are the ingredients of what King called a “true peace,” which King contrasts with a negative peace where a lack of social strife exists in the midst of injustice or social estrangement. There is an important lesson in this for depolarization advocates like myself as well as social justice activists. Some depolarization advocates desire social goodwill and brotherhood so much they are willing to tolerate injustice in order to achieve them. This is a fool’s errand. One cannot hold goodwill for a person whom they allow to be treated unjustly and brotherhood requires reciprocity and trust, both of which, in turn, require justice. Alternatively, some social activists focus exclusively on securing justice and obstruct community formation in the process. Justice detached from brotherhood and goodwill falls short of community and agape.

Here we see the multidimensionality of agape as a creative force. It is not merely the motivation to create community, but the ingenuity to secure justice without sacrificing goodwill and brotherhood. For King’s civil rights activism this creativity often took the form of nonviolent protest The aim in these protests was not to “defeat or humiliate the opponent, but to win his friendship and understanding” (2010 [1958], 90). Nonviolent protests forced white America to face the corruption in their social systems and their own hearts while avoiding revenge or returning the injury black Americans had endured. But the creativity of agape isn’t restricted to protest. Bringing justice and reconciliation where there is injustice and estrangement is the goal, determining the method needed to achieve this takes wisdom.

Here in Kansas City, the gulf between King’s vision of the beloved community and the realities of our city are stark. Residual effects of the city’s racist history can be seen in white and black disparity in poverty, housing, healthcare, education, and imprisonment (Griffin 2015, 181-2). We are among the top major cities in the U.S. for homelessness and homicides. In other words, we are not seeing the community love pushes us to desire.

So, as King was fond of asking, where do we go from here? Creativity is, by nature, resistant to formulation but there are some methods we can learn from King. First, there must be an unflagging commitment to creating community. According to King,

agape is love seeking to preserve and create community. It is insistence on community even when [some]one seeks to break it. Agape is a willingness to sacrifice in the interest of mutuality. Agape is a willingness to go to any length to restore community. It doesn’t stop at the first mile, but goes the second mile to restore community (2010 [1958], 94).

The inexhaustible drive to create community is reflected in God, agape Himself: “The cross” writes King, “is the eternal expression of the length God will go to restore community” (2010 [1958], 94).

Creating community from a broken society is not an easy task. It requires dedication and a willingness to suffer. For suffering itself, according to King, can be “a creative force.” In fact it was this method, the willingness to suffer, that prompted some of the most effective nonviolent protests in the civil rights movement, such as the “Bloody Sunday” attack on marchers in Selma, Alabama.

Another method is intentional contact across differences. In Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community?, King’s last major work before his death, he wrote:

Like life, racial understanding is not something that we find but something that we must create. Whatever we find when we enter these moral plains is existence; but existence is the raw material out of which all life must be created. A productive and happy life is not something that you find; it is something that you make. And so the ability of Negroes and whites to work together, to understand each other, will not be found ready‑made; it must be created by the fact of contact (2010 [1967], 28).

I take this to be true of all human differences. Understanding those who are different from us is not something we unintentionally find, as if it already exists and we can merely stumble across it. Rather, an understanding of those who are different from us is something that we must create and the crucial step in this process is contact.

I believe that by drawing on King’s methods of being willing to suffer for the cause of community and being intentional in our contact with those who are different from us, especially those who think and act in ways we disagree with, we can create the beloved community. King and other civil rights activists faced physical abuse, threats, and murder. This is a suffering most of us will not have to endure. But contact across differences, especially where justice is at stake, is seldom easy. To be angry at injustice is good. But anger is simply the moral alarm bell that tells us something is wrong and needs correcting. Once the wrong has been identified anger must be controlled if one is to correct the injustice with goodwill and brotherhood intact. This will require a willingness to suffer the pain of pushing past hatred and resentment to a place of understanding; it will require a willingness to suffer insults and rejection; it will require a willingness to suffer the discomfort of admitting when it is you who are wrong.

King believed love is a motivation to create a community where there is justice, brotherhood, and goodwill. This is not our community, so we must allow love to motivate us to seek it. To do this we must be willing to suffer for it, not just in big ways, but in small, mundane ways. This MLK Day, take time to reflect on those things that make you angry and the people you disagree with, maybe even to the point of estrangement. Where there is injustice, commit to change. Where there is division, create understanding.

Further Reading:

Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story by Martin Luther King, Jr.

Strength to Love by Martin Luther King, Jr.

Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community? By Martin Luther King, Jr.

References:

Griffin, G.S. Racism in Kansas City: A Short History. Chandler Lake Books, 2015.

King, M.L. Stride Toward Freedom: The Montgomery Story. Beacon Press, 2010.

King, M.L. Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community? Beacon Press, 2010.